Jul 20, 2013

This morning, I found myself running down the middle of an empty highway in rural France at 5 AM. A litany of WTF’s rang through my head.

The sun rose, gently, turning attention to row upon row of freshly-cut crops stretching exorbitantly toward the horizon. Beyond softly rolling hills in the distance, there was the faint quilted pattern of a tiny village, cows and baguettes and all. Except for the thin ribbon of a two-lane highway, it was vague what century this place haunted.

I remember hypothesizing here a month ago, in the car-loathing aftermath of backseating several thousand miles around the US, that I was finally done with travelling for a while. I had just arrived back in San Francisco, unpacked my backpack, fixed my bike, and started interning at the EFF.

A week later, realizing that I could work remotely and that there were better places for human existence than 2 blocks from Market Avenue, I bought a plane ticket for Europe. I had hatched some sort of hazy half-plan to ditch the life I had constructed in SF and backpack around a continent that I had never visited, full of languages I couldn’t speak, until my visa ran out in 3 months’ time. I would carry as little as possible, find like-minded hacker-type people to stay with, and spend most of my time writing code for the EFF, undeterred by distractions like understanding what other people were saying to me. Plus, since I wasn’t paying San Francisco cost-of-living prices and sold my Burning Man ticket, I would probably save money overall. Nothing could go wrong.

After sleeping through the entirety of the flight from SF to Paris while cradling a Kindle that I had intended to use, I unloaded myself into a subway at CDG, got off in the 6-euro-couscous-vendor district, and promptly reached the apartment of a Paris-dwelling ex-housemate who I barely saw the entire time. My impression of Paris from 2 days of aimless wandering is of a city whose historical and cultural significance is completely blighted by the lack of any usable WiFi except at McDonalds. I did not like Paris or find it fit for habitation, needless to say.

Fortunately I was rescued by a group of old friends, who invited me to stay and work with them in (1) a former convent turned into (2) an artist co-op / workspace owned by (3) a man with a pet peacock in (4) a tiny rural town in northern France. Several times a day, I will remember each of these four things in turn and suddenly feel like I’m dreaming.

This is my room:

And this is the view:

The night I arrived, we grilled meat and vegetables in the garden, with wine and baguettes aplenty.

The peacock made a cameo.

I took a wander around the convent and basked in its eccentricities.

I started settling into a routine after a couple days. It goes something like:

5 AM: Wake up

5:30 AM: Go for a run as the sun rises.

6:30 AM: Breakfast, shower, etc.

7 AM: Start work.

3 PM: Go to bed.

7 PM: Wake up, eat lots of baguette, start work again.

10 PM: Cook and eat dinner with friends.

11 PM: Try to work, mostly end up emailing/IRCing with people in the US who are now awake.

2 AM: Go to bed #2.

This is almost ideal, except that the only grocery store in town is 40 minutes away by foot and closed whenever I’m awake and not work-binging.

I like it here a lot. It’s quiet. There aren’t many people to talk to, since my friends are busy hacking away on a P2P video-sharing project all the time. I get to read a lot. Javascript has become fun – oh wait, maybe I have Stockholm Syndrome.

Jul 5, 2013

So it happens that every time you access a URL that starts with “http://”, anyone on your local network can see what you’re doing with almost no effort worth writing about. This includes the page itself as well as any information that you’re transferring, like credit card numbers and passwords (which are hopefully encrypted). It’s worth reiterating that this isn’t difficult at all, even if your network is WPA2-protected, as most supposedly-secure WiFi networks are nowadays.

This sounds like quite a displeasing predicament for those of us who find ourselves using shared wireless networks every day (aka, all of us), but I get the impression that most Internet-users don’t understand exactly how simple it is to casually sniff HTTP traffic. So, in hopes of convincing you that it *is* in fact simpler than using any OS X package manager successfully, here is the absolute fastest, easiest way I found to reliably eavesdrop on HTTP traffic on most local networks. It should take less than 5 minutes to set up on your Linux thing (maybe also your Mac thing, but I haven’t tried) and is straightforward to understand.

(This is intended for education purposes, and also for encouraging more people to use HTTPS instead of HTTP whenever possible, maybe even via the browser extension that I’m contributing to this summer. More on that in a bit.)

- Run the following to install some packages that we need. dsniff is a collection of various traffic analysis tools, of which we’ll only use arpspoof; see here. tshark is a nice terminal-based packet analyzer; tcpdump also works.

- apt-get install dsniff

- apt-get install tshark

- Turn your machine into ip-forwarding mode as root by flipping a 0 to a 1, or else people on your network won’t be able to see their websites. Don’t do this step if you actually want to launch a denial of service attack, I suppose. Also you might want to remember to turn it back to 0 after you’re done.

- echo “1” > /proc/sys/net/ipv4/ip_forward

- Run the following commands as root on a WiFi network. To find your IP address, you can run ifconfig and look for the wlan0__ inet addr. To find your router’s IP address, you can do something like run traceroute google.com and pull out the IP address from the first hop, which is likely to be 192.168.x.x.

- arpspoof -i [your IP address] [the router IP address]

- tshark -p port 80 -i wlan0 -T fields -e http.request.method -e http.request.full_uri -e http.user_agent

And voila, the second command spews out a stream of HTTP addresses that people on your network are accessing, along with the request method and the type of client software used. This is just the start; you can read the manpage for tshark to figure out how to pull more detailed info from the packets and then start writing scripts to modify them before forwarding them along. Ex: appending -e text will show HTML data as text from the webpages.

What we’ve done so far is:

- Perform a attack called ARP spoofing on the router. Essentially, we trick everyone on the network into thinking that your computer is the router so that all the traffic intended for the router goes to your computer instead. This is straightforward since ARP doesn’t include authentication mechanisms.

- Use tshark to extract interesting information from the packets that we’ve intercepted.

- Forward these packets along to their intended destination so nobody detects our spying.

While sniffing packets as they floated by on a warm summer night in the attic of a Berkeley farmhouse in the process of testing this out, I could see which HTTP websites my housemates were accessing, what apps they were using on their phones, and what desktop clients they were running without them ever noticing. With a small amount of additional effort and a large amount of additional malice, I could have manipulated their traffic to interchange the titles of Wikipedia articles or whatever else I wanted, the possibilities bounded only by my imagination / knowledge of regular expressions.

[Note that although WPA2 encrypts data that goes between the router and devices on the network, this clearly doesn’t prevent eavesdropping via arpspoof by other devices that have access to the network. Stack Exchange explains that by operating at a layer above that at which WPA encryption occurs, an arpspoof attack causes the data to instead be encrypted for the attacker’s device instead of the router.]

Sadface time. On the other hand, none of the above works if you’re using HTTPS, where the S stands for “secure,” because in that case traffic is encrypted between you and the server you’re trying to reach. On the other other hand, outgoing HTTPS requests from your device can still be subtly converted to insecure HTTP via an attack called SSLstrip that makes use of arpspoof if you try to reach an HTTPS site by redirecting from HTTP. On the other other other hand, you can download the EFF’s HTTPS Everywhere extension for Chrome/Firefox, which rewrites HTTP URLs to HTTPS before you try to connect to the HTTP site. On the (other)*4 hand, there’s some problems with SSL in practice because of intermediate certificate validation carelessness and so forth. I’m now out of hands.

Jul 4, 2013

Last month, CNET announced that Facebook is working on implementing a property called forward secrecy in its encryption of user data. The article is pretty long, but the gist of it is:

- Forward secrecy is good news, at least theoretically. Right now, when you send data to Facebook’s servers, your data gets encrypted so that someone who intercepts your data can’t read it unless they have Facebook’s secret key. However, if an eavesdropper is recording your messages now and somehow gets the secret key in the future, they can go back and decrypt all your encrypted communications. Forward secrecy in an encryption protocol, by definition, means that if the secret key is compromised, your communications are still safe from decryption.

- Google is the only major web service that has forward secrecy in its encryption protocol enabled by default. Most services don’t do this because it’s computationally expensive.

- The leaked slides about the NSA surveillance program, PRISM, suggest that the NSA is tapping into Internet connections and collecting data in transit between your computer and Facebook’s servers, or at least that this is possible.

- Once your data is collected by the NSA, it can probably just sit around forever. That gives plenty of time for Facebook’s secret keys to be brute-forced or obtained by the NSA through a court order. Without perfect secrecy, all your data can be decrypted once this happens.

So in other words, Facebook is implementing an extra security measure to protect data in transit from users to their servers, and this announcement comes at an opportune time in light of the PRISM revelations in early July.

But data in transit isn’t the only kind of data that needs to be protected! What about data at rest?

To clarify what I mean here, let’s think about the flow of data from you to your friends when you make a FB post. This is simplified, but it goes something like:

- You type a message in a text box in your web browser and hit send.

- Your browser encrypts that message before it leaves your computer and goes on its way to a Facebook server.

- Your message travels over the Internet in encrypted form.

- Your message reaches a Facebook server, which decrypts the message and stores it in a database so that it can be retrieved later to be shown on your profile, in your friends’ news feeds, in searches, and so forth.

In Steps 3 and 4, your data goes from in transit to at rest. Here’s a handy diagram from Wikipedia that distinguishes the three states of data, which I’m simplifying into two by merging “data at rest” and “data in use”:

Three states of data.

Nowadays, it’s expected for major web services to encrypt all data in transit by default using HTTPS, which uses the SSL/TLS cryptographic protocols. This is generally done by using a persistent private server key for both authentication (verifying the server’s identity) and encryption (encoding the data so that only the server can read it). This does not provide forward secrecy, and all encrypted messages are compromised once the persistent server key is found.

Facebook’s announcement, which follows one by Google in 2011, reflects a recent shift toward supporting forward secrecy by generating ephemeral Diffie Hellman keys for encryption during each session. A persistent RSA key is still used to authenticate the server. The ephemeral keys used for encryption, however, are not stored beyond a session. Thus, even if the persistent key is compromised, data that has been obtained through eavesdropping on an Internet connection is still safe from decryption.

However, recall that in Step 4 above, Facebook decrypts your data and stores it in a database, presumably one that is password-protected or has some other security measure that lets a trusted set of people access it (database admins, for instance). At this point, your data is just sitting around in decrypted form, protected by whatever-FB-does-to-protect-its-servers. It would be impractical to do otherwise because performing encrypted query operations efficiently is hard maths, and basically the definition of a web app is something that stores data and performs interesting/useful queries.

With Facebook’s announcement of support for forward secrecy in TLS/SSL, we’ve been assured of increased attention to security for data in transit, but this of course says nothing about data at rest. Indeed, it seems that the NSA surveillance leaks have sparked relatively little discussion of policies at companies like Facebook for securing data at rest. That’s surprising to me, because the oft-spoken phrase “NSA back door” vividly suggests that the NSA is in the trusted set of people who have access to the decrypted data in servers at FB, Google, and so forth.

To be clear, forward secrecy is effective against a particular adversary model, namely wiretapping. Although the CNET article points out that the NSA is probably doing a bunch of wiretapping these days and has agreements with Internet service providers to facilitate such, I assume it’s still easy for the NSA to walk up to someone at Facebook and demand access to the database. In fact, regardless of how secure data is while in transit, it basically always needs to get decrypted on the server side in order to be useful for a web service. As long as it’s easy for the web service to access the decrypted data, it’s easy for the NSA to do so as well*.

*Barring policy changes that would legally prevent surveillance. Even so . . .

In short, there probably exists no NSA-proof cryptographic protocol for securing data at rest so long as companies agree to comply with gov-authorized surveillance programs. Forward secrecy doesn’t seem like much of a deterrent to PRISM in that case.

But in terms of protecting our privacy from attackers who aren’t government spying agencies, the security of data at rest matters as much as, if not more than, security for data in transit. Unfortunately, whereas TLS/SSL is an established and widely-used standard for encrypting data in transit (albeit flawed in practice), procedures for securing data at rest seem to vary widely between companies (see Appendix A). These procedures are often described in vague terms if at all. For instance, one service simply states that it “provides multiple layers of security around your information, from access protected data centers, through network and application level security . . . Sensitive information, such as your email, messages and passwords, is always encrypted.” The methods of encryption, whether they are applied in transit or at rest, and other important details related to the security of the service are left out.

It’s hard to blame the product description writers for omitting these crucial details, because most users simply don’t care as long as they feel reasonably secure. It’s easy to feel secure with assurances like the ones quoted above, and news articles about implementations of forward secrecy in the works at FB. And then you get things like Twitter sending passwords in unencrypted form or Apple failing to properly authenticate SSL certificates or a whole Tumblr blog of websites that store and send passwords in plaintext, oops. There’s a difference between feeling secure and actually being secure on the web, clearly, but paranoia is tiring and you should probably go check on the 12 Facebook notifications that you got while reading this blog post.

===========

Appendix A: A Brief, Non-Representative Survey of Company Policies for Securing Data at Rest

In the course of researching this blog post, I made a post on a certain social media site asking my friends in tech about how their companies secured non-sensitive data at rest, where non-sensitive data includes user-to-user communications and metadata (but not passwords, SSNs, and financial data). The few answers I got were more sophisticated than, “In plaintext, on a password-protected database,” but I suspect there’s some selection bias here. Anonymized responses below.

___

I’ve worked with so many apps, and it’s almost always a database behind a firewall. I’ve occasionally built systems where financial data was stored in some more secure way: one, where financial data and transaction processing happened on a separate box with no services and a very minimal API (to limit exposure), and where it was impossible to retrieve the sensitive information via the API.

The other one actually encrypted data using a key that was secured with the user’s password. It was re-encrypted using the user’s session on login, so the cleartext was only available when the user was logged in, during a request from that specific client. In this way, sensitive information was protected from our staff, and from an attacker, except that anyone who was actively using the system would be exposed (to a reasonably sophisticated attacker).

None of these ideas provide protection from a government, though. Client-side encryption doesn’t really, either. Just look at what happened to Hushmail. I really want there to be some trustable encryption API in the browser, so that client-side encryption for web apps could be a real thing.

___

We actually encrypt (with a separately stored per-user key) all of our user message content. It makes me way way more comfortable debugging problems that come up in production knowing I’m not going to accidentally read a message that was meant for a friend or co-worker. It’s pretty low-effort and low-resource-intensity for us to do this so it seems silly not to.

I guess the tradeoff is that for somebody like Facebook they’d lose the ability to do queries in aggregate to make advertising or similar decisions based on content.

. . . the keys [for encrypting messages] are stored with symmetric encryption. It defends us against outside attackers getting use out of dumps of our database but in theory with access to the layer that gets the messages and has the keys the encryption doesn’t matter. The practical limit when we’ve looked at doing more is one where as long as our site can display your messages then there’s some set of our infrastructure an attacker could use to read those.

___

We use client-side encryption with client-generated keys for user history/bookmarks/passwords, etc. So adding a device to access said data involves JPAKE (key exchange) via our servers (which are treated as an untrusted 3rd party).

This means syncing is hard, but we associate each record with a record ID and sync them if the hash changes.

For telemetry, we use anonymized data – uploads are linked to a UUID that only the client stores locally.

Jun 10, 2013

Large American cities breed complacency. We grow up in the suburbs, we move to the cities after college, we get jobs and buy apartments and curate routines. We find comfort in the monoculture of coffeeshops, the ubiquity of free wifi and indie periodicals. College students flip through biology textbooks, their thumbs skimming over blue-framed iPhone screens.

The small town of Marfa, Texas subverts urban complacency. The streets are hot, desolate, effortlessly dusty. Buildings arranged sparse like haiku lines. A lone gas station on the corner offers only two varieties of bottled water.

Upon closer inspection, a startling fraction of the blank-faced single-story buildings in Marfa reveal themselves to be contemporary art museums.

At night, the heat departs the sidewalks reluctantly like rising angels on their way to the dentist. Warm lamplight floods the streets, supplanting the blues and purples of a late desert sunset. We walk to a bar down the block, where a high school graduation party is underway. The high schooler is nowhere to be found, but his family members run plentiful. 2-4 middle-aged couples dance the macarena as the DJ shuffles windows around on a laptop.

At 11:20 pm, an old man hands us beers and drives us down a dark lonely highway in an obnoxiously loud bus. He herds us out into a field of moonlit grass rife with ant hills. As we shiver in the stiff breeze, he points into the distance at a pair of faint pulsing lights, orange and yellow, bobbing on the horizon. The Marfa Lights, he says. Nobody knows what they are, not even the scientists from Austin who came and studied them for months. Some say aliens; others say cars on the highway.

“What happens if you look at them through a telescope?”

“Well you see the same thing, only bigger.”

The next day, we are fed sweet French toast and taken to art. We walk from bungalow to bungalow, gazing. There are rows upon rows of aluminum blocks whose gleaming surfaces cast geometric deceptions, chaotic multicolored masses of twisted metal, rooms suffused in unearthly neon light, cartoonish paintings of tesselating women, and an abandoned Soviet schoolhouse left in disarray.

Marfa feels like an alien outpost in the morass of stereotypes that is America.

May 30, 2013

Tonight, if I’m lucky, I’ll sleep on this soft green velvet couch where I spent 80% of my junior year of undergrad proving the existence of dark matter, determining the electron charge, reading papers on adiabatic quantum computation, and overfitting most things that I encountered. If I’m unlucky, I’ll stay up the whole night and hack away at some Python scripts testing a hypothesis I have about bitsquatting, or maybe I’ll jailbreak my new Kindle, but probably I’ll find myself brewing a kettle of tea and nostalgically gazing at the rain falling on the porch where I used to sit and read books in summer.

I’ve spent almost a month in Cambridge, MA, the first city that ever felt like a home to me. I arrived in 2008 for the first time with a couple bags of clothes and no concrete idea of how to use an electric dishwasher. I was put in a dorm room at MIT (Random Hall, to be precise) with huge windows and a sponged-on periwinkle paint job. People outside deep-fried oreos and broccoli. And then began the college move-in rituals: running down the street to the pharmacy to buy soap, laundry for the first time, canned soup, roommate reading Sylvia Plath, trying hard not to brush against the walls of the shower stall, purchasing textbooks for the first and last time.

Four years went by. I climbed roofs, wore scarves in winter, carefully checked proofs, and listened to people when they talked about feelings. My time ran out; I flew to San Francisco and lived in places not intended for human habitation. Sometimes I felt alone because nobody was around. At other times, I felt alone because I couldn’t establish a sincere connection to the people around me. The plans that I had made for the West Coast started to dissolve, and I realized at the age of 21 that there did exist something akin to a soul, in the strict sense of an identity capable of empathy. I fell out-of-practice with the ability to feel empathy for others. The idea of having close friends was appealing enough that I tricked myself into thinking that it was frequently realized, but in actuality I felt isolated from humankind much of the time.

This proved to be non-problematic until I woke up one day feeling like the future wasn’t going to be better than the past. This was one of the most precisely terrifying thoughts that I can remember having, precise in the sense that it is extremely well-defined and has immediate consequences for how one approaches life on a day-to-day basis.

I left San Francisco and was vague about the reasons to almost everyone who asked.

Almost miraculously, things got better in Cambridge. I spent time with an old friend with whom I’ve had a twin-like understanding in the past; in a glowingly inevitable moment, our identities seemingly merged into one. I went for long runs in the middle of the night. I sat in a church parking lot as the sun was setting, gluing spray-painted floppy disks to a friend’s car. Someone that I hadn’t talked to in years explained her dreams to me and then explained the structure of the human ear, which led to the discovery of a mind-blowing balancing trick. A friend from San Francisco visited, and we unexpectedly lost a couple days with each other coding and walking around the city and watching short films. I went to an outdoor arts festival in Delaware and kept a fire for friends wandering past in the middle of the night.

In a few hours, I’ll be on a plane headed to Austin, TX, where the start of a road trip awaits. Austin -> Marfa, TX -> White Sands -> Grand Canyon -> Joshua Tree -> LA -> Big Sur -> SF -> Seattle. And then back to SF.

May 30, 2013

Vegan food everywhere! Taco bars with speedy wifi! Fresca margaritas! This is the American Dream INCARNATE.

Tomorrow I shall go explore the city and die of heat stroke.

May 24, 2013

I’m just not that big a fan of usability, at least not for myself. To be clear, I do care about things being usable, but only enough to delay the eventual onslaught of social alienation. I drink water out of bowls, but only when the apartment is out of cups; I use xmonad as my window manager, but not at potlucks.

Thus far in my computer-using life, I’ve never owned a monitor. I don’t have a smartphone, so everything I do is on a pint-sized Thinkpad X220: writing, coding, ebook reading, garden-variety Internet browsing, photo/audio editing, bike trip navigation, sleeping, etc.

But recently, I was in the lovely town of Cambridge, MA on a warm spring day, staring out the window of a tired blue house at trees heavy with the impending procreation of innumerable songbirds, feathers washed in ecstatic glow of pollen. Mysterious stirrings of latent desire dripped from the stretched-out sky. Something changed inside me. Suddenly I felt like editing config files.

So I shut the window and did that for a while, maybe a couple hours or until I started showing symptoms of Vitamin D deficiency, don’t really remember.

At the end of this abortive config-puberty, I threw everything on Github because typing ‘git push’ releases a lot of dopamine in my body and apparently I like that.

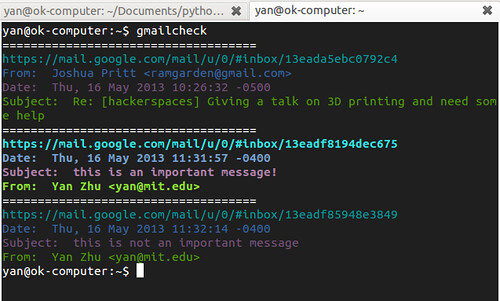

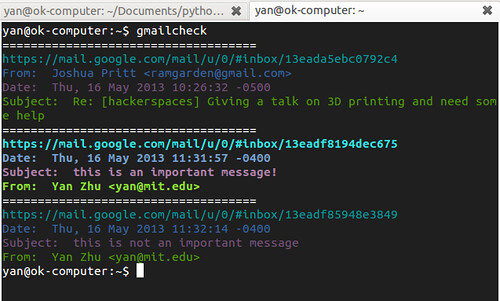

The observant git tree-traveler will notice that there’s a Python script called gmailcheck in that repo. This is something I’m glad I wrote, because it solves a real problem without being overly complicated.

The problem is this: I spend most of my productive work time in the terminal, which is usually the master window in my tiling window setup. I usually also have a browser window open for Google searches. Using gmail, as it turns out, is hella dumb in a window of this size. Furthermore, checking gmail in the browser usually leads to an unending parade of distractions as I start to add events to my calendar, respond to some emails that can wait, click on links that friends have sent, open up Noisebridge-discuss threads with titles like “Who put mercury in the laser cutter? Also, kindergarteners visit TUESDAY,” etc.

On the other hand, not checking email at all is not an option, since my phone is usually useless, and anyone who needs to tell me something important is advised to do so over email.

Essentially, I needed something that would show me whether I had important emails in the terminal. Maybe like Mutt but with the removal of all features that could possibly lead to distractions.

Seems like a pretty simple Python script, and it was. Gmailcheck v1.0 will show you basic information about unread emails from the last hour, or whatever time you want to hard-code in for now. I added some extra bells and whistles, like hipster colors and highlighting of emails that gmail auto-labels “Important.” If you want to actually respond to an email or do other fancy stuff, you can click on the link and just go to gmail’s web interface.

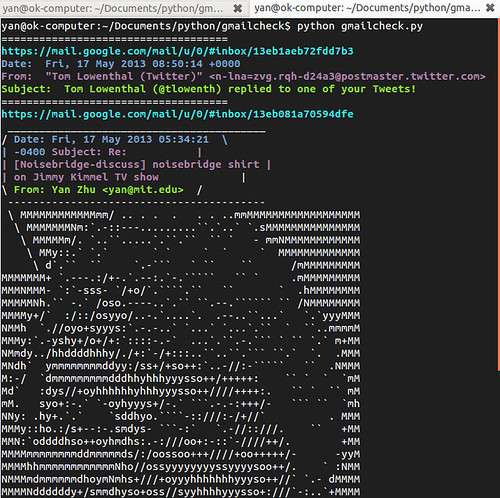

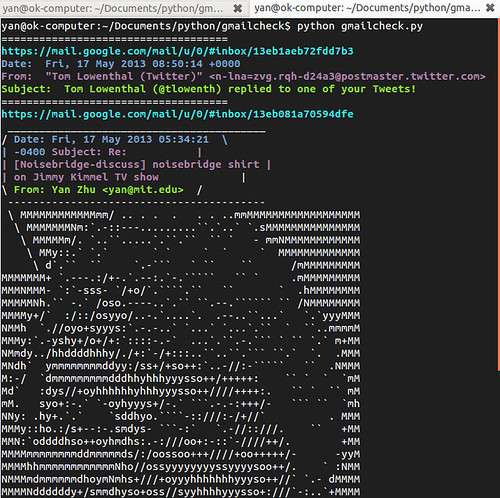

Upon reaching this milestone, the next logical thought that occurred to me was, “How do you properly evoke the spirit of emails on the Noisebridge mailing lists?”

The answer is that you print them being said by a huge ASCII-art rendering of Tom, Noisebridge secretary and (before this happened) a friend of mine.

I guess I still don’t care about usability.

Apr 24, 2013

In Jan. 2013, someone cut the brakes on my bike while it was locked up oustide Noisebridge and stole the handlebars. This was a major nuisance, since my ankle was sprained at the time and bicycling was my sole means of getting around the city.

It was also a hard time for other reasons. Two people that I cared about had passed away the previous week in unrelated incidents that caused a great deal of shock for those who knew them. In this context, seeing my bike forlorn and violently stripped on the sidewalk made me feel unsettled in a way that made me not want to try to fix it.

One of the few things that kept me going that week was organizing the Aaron Swartz Memorial Hackathon at Noisebridge and acting as the coordinator for a worldwide series of similar hackathons. The Noisebridge event itself went off better than anyone expected and was one of the happiest points of my previous year. I didn’t keep close tabs on the hackathons around the world, but it was heartwarming to receive enthusiastic emails from hackers from faraway places like Bangalore and Zagreb, discussing projects they wanted to work on at their local hackerspaces in memory of Aaron.

During the hackathon, I discovered SF’s online treasure trove of SFPD crime incident reports and other open data. I downloaded all the crime reports from the last 10 years and, for the heck of it, made a map of all the bike-related incidents.

View Larger Map

Lesson: don’t park your bike in SF, except for on Treasure Island, the Presidio, and this one weird patch near 15th and Folsom.

And here’s a map of all the prostitution-related incidents, because I had a hunch that this would produce clearer neighborhood boundaries.

View Larger Map

These would be more meaningful if they were heat maps or normalized by density, but you know, life is short.

Jan 20, 2013

[originally posted to https://yan.jottit.com/ on 1/20/13]

Grad school was alright. I liked the people, I liked my research, and I liked the security of knowing exactly what I was going to be doing for the next 5-6 years.

Grad school in experimental physics was the easy choice for me. I had a hella fly academic track record, liked doing research, and reportedly got one of the two highest scores in experimental physics my year. I got into all the grad schools I applied to and lots of fellowship offers as well.

But what bothered me was that it was a convenient choice but not a fully deliberate one. It paid the bills, gave me health insurance, and allowed me to live near San Francisco while having a decent amount of free time. However, I was pretty sure I had zero interest in going into academia as a profession. So grad school was mostly a way to stall while figuring out what exactly I wanted to do with my life.

Then I got tired of stalling and not doing anything that felt productive in the meantime.

It got to the point where I finally decided to walk away from the NSF fellowship, the sunny apartment in suburban paradise, the guaranteed 6-year stipend, the free enrollment in Stanford classes, the health care, the gym access, and the prestige of getting a Physics PhD from Stanford in favor of being homeless, unemployed, and perpetually uncertain of tomorrow.

The last month or so has been full of stress, disappointment, and self-doubt, the pains of a transition to life without externally-imposed structure. There’s also been unexpected validation. It feels really, really good, almost glorious, to read a paper or teach yourself a new skill knowing that you aren’t doing it for any reason other than because it really deeply matters to you. I realized that too much time in my life thus far has been spent on tasks that I did in order to pass tests, get jobs, and prove myself to others.

As soon as I decided to leave Stanford, I had about 393849394 projects that I wanted to work on day and night. I wanted to brush up on a couple programming languages and learn several new ones, build a start-up, read up on anarchist theory, fix all the problems in the way scientists do science, take an online class in computer networks, facilitate open access to journals, help develop cryptographically secure tools for activists, promote social justice, start a warehouse living space, contribute to open source code repos, read papers on neural networks, blog about data science, and make tasty vegan food for friends. But I never could focus entirely on doing any of these things becaused I was too scared of not having a job for too long.

These days I alternate between feeling excited about doing these projects and feeling distracted/worried that I’ll never make a living at the same time.

This issue is unresolved as of this writing. Intellectually, I’ve convinced myself not to worry about getting a job for now (I can live reasonably for almost a year on savings, anyway) and focus instead on projects that’ll have a positive impact on the world. It bothers me that this isn’t a sustainable way of living, though, and I’d rather fix that sooner than later.

Nov 24, 2012

40 minutes in Tribeca on the way from Newtown to Boston

is all we have

before the parking meter runs out

so I transcribe the light of the setting sun in shorthand

(a cricket clutter of shutter clicks)

while you look for a bathroom.

the sun is running out

like a roll of toilet paper

waning into weary ribbons

as it soars toward heaven,

forgetful of the symmetries of the parabola,

the ache in the arms of your neighbor’s sycamore.

we leave with eight minutes to spare.

skeletons of metal and glass rip the skin of the sky,

autumn spread thick like marmalade

on this slice of highway.

the jar is running out

but the grocery store is closed.

87% of bathrooms in Tribeca are for employees only.